The Performance of Objects

I’m going to the Ashmolean because my therapist made me. That’s not entirely true but it is the story I told myself as I grumbled up the stairs of the beautiful building last week. The fact is, I don’t like going to museums.1 I appreciate them, I recognize their role in society and culture, I even pay for some memberships to a couple whose missions I appreciate. They are vital for conservation, they can inspire and educate, when done well they can shift the tides of representation.

But I read too slowly to fully take in gallery information, my back hurts when I wander sedately on hard floors, the lights make me yawn, I’m usually overstimulated, and I hate watching people stare at art and artifacts through the lenses of their smartphones. My brain has classified them as a thing you do on vacation to pass the time until the next meal.

My therapist and I are at odds about this, in a way that I think is only therapeutically appropriate because we’ve been together 18 years. She loves them. She seems hellbent on getting me to love them. She has not succeeded. But when I told her about my summer in Oxford, she insisted I had to go to the Ashmolean.

It’s beautiful. It’s a beautiful building with beautiful items curated beautifully. And I still didn’t want to be there. The vague concept that hit me as I wound my way past pot after pot, vase after vase after fragment after tool after wall hanging, was that somehow museums remind me of the love I’m losing for film, television, and theater: I don’t want to watch the acting of emotion, I want to watch the real-time emotions themselves. I don’t want to watch the interpretation of stories, I want to watch the possessor of the story recount their life. Forget WC Fields, bring on the children and animals - they’re actually living in this moment right now. I want to watch that.

Museums strike me as a performance of objects. (And I’d be remiss to leave out that often the acquisition or retention of those objects was deeply harmful and problematic in the first place - this isn’t a piece about artifact theft and repatriation but it does hang over any discussion of these institutions). Though I may enjoy aspects of the performance, I’m bored by the show, and am left feeling removed from direct experience.

The only way I can figure out to feel the Right Now of objects, as opposed to their performance, is to sketch them. I suppose drawing something on display is a bit like interviewing it - I ask it questions of its form, it tells me what it is right now that can’t be written on the placard.

Just yesterday I was introduced to a quote from poet and essayist Paul Valéry, “To see a thing truly is to forget its name.” The thingness of any subject drops away in drawing, replaced by an exploration of light, dark, form, and contour. Twenty minutes spent drawing one sculpture gave me more sense of presence and inspiration than the previous 30 forcing myself around the halls.

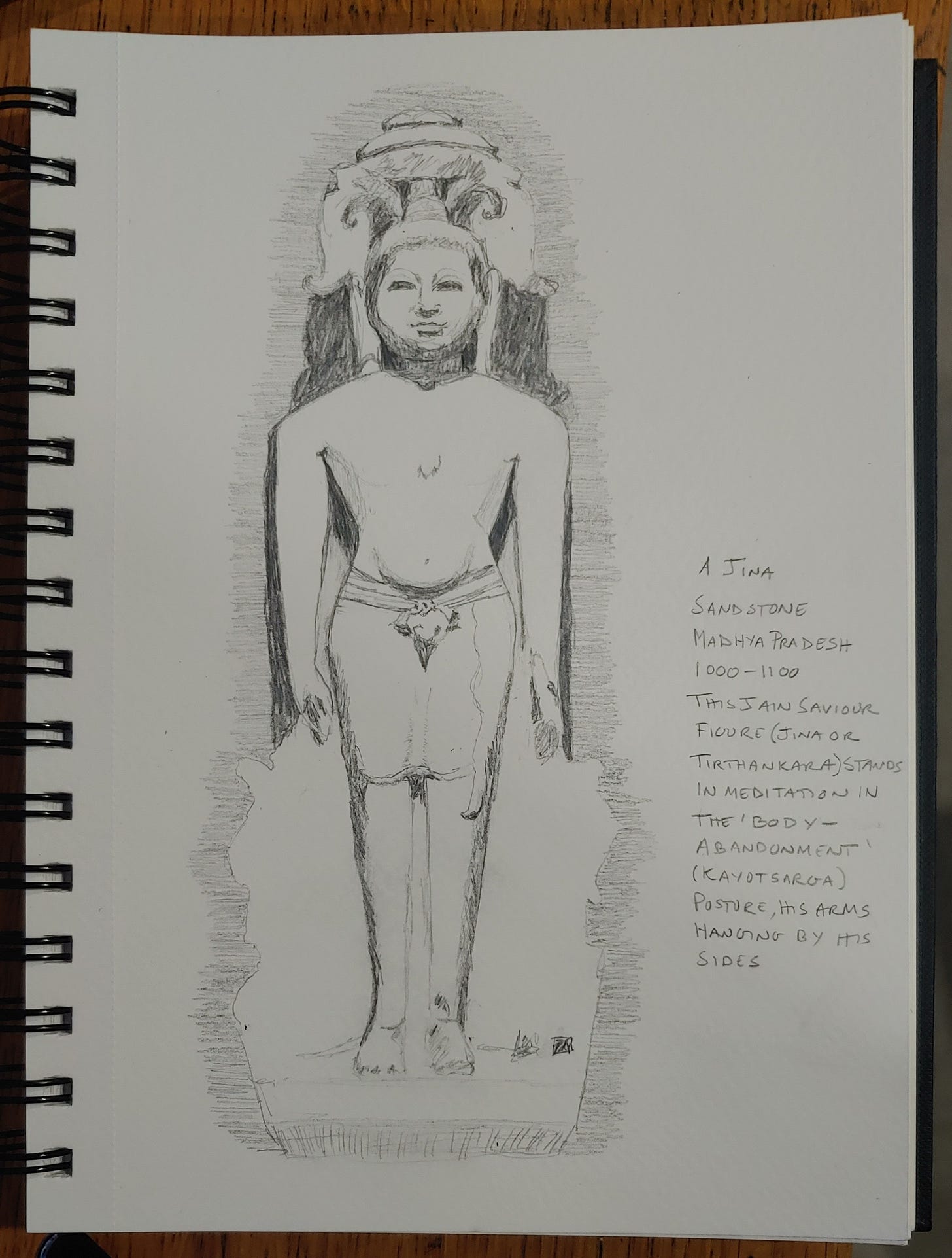

But perhaps it is fitting, then, that the piece I chose to draw - to connect me somehow to the world of people who like musuems - was this sandstone Jina or Tirthankara from the Jain tradition. I was struck by his soft belly, and the expressiveness of his face, and was later moved when I read about their significance. As Wikipedia quotes from the Encyclopedia Britannica (now there’s an ancient artifact), they are beings “who have conquered saṃsāra on their own and made a path for others to follow.”2

Perhaps this figure, standing in the ‘body-abandonment pose’ was asking me to stop defining museums, performance, interpretation and authenticity, objects and experience as different, defineable, solid, separate things. Perhaps all objects stop performing when looked at closely enough.

The exception to this is science museums - places where there’s a lot more doing and a lot less reading.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tirthankara