Wheels & Waves

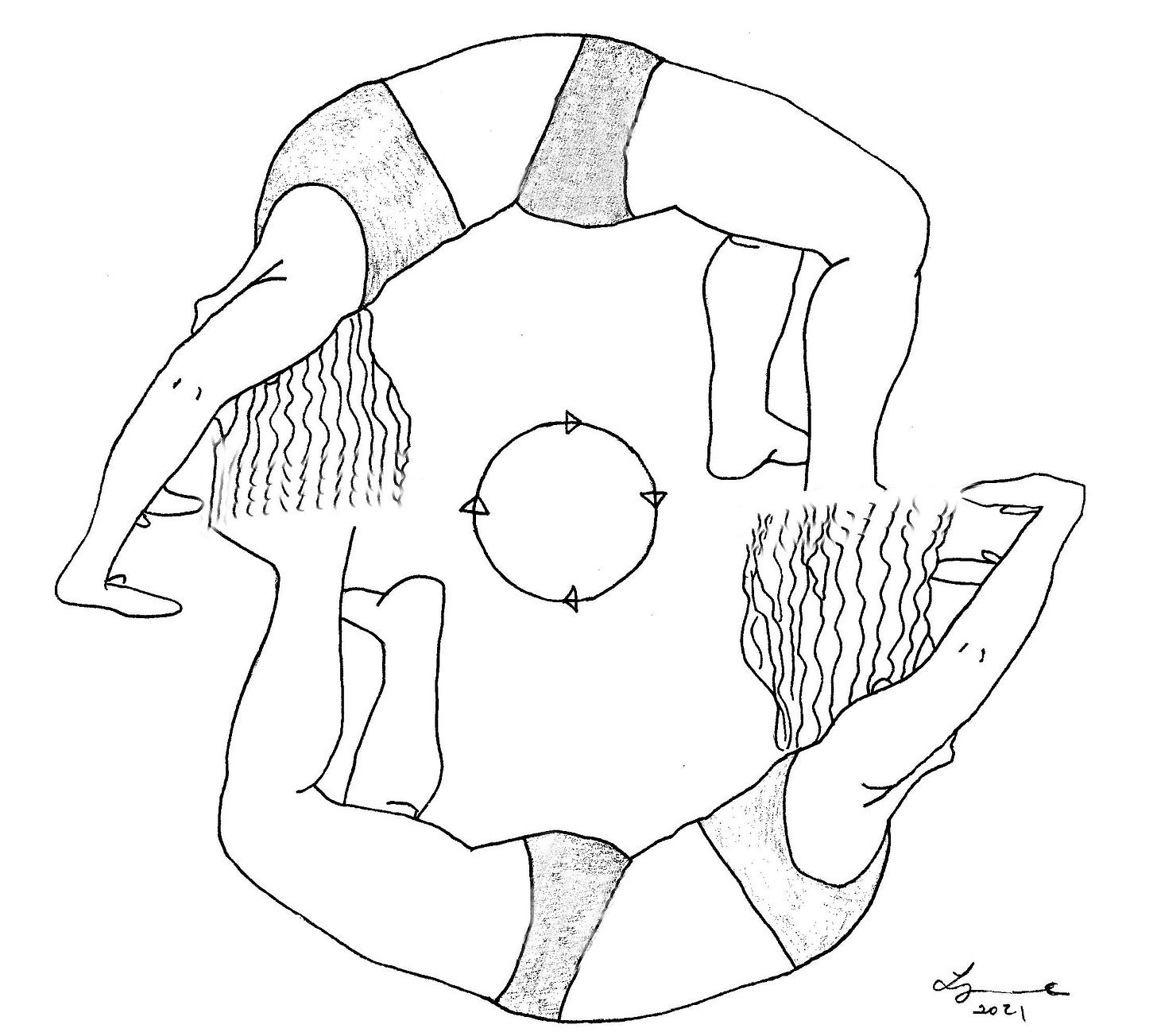

I found it impossible to get myself to write this weekend, so I thought I would share something I did this summer for my Creative Nonfiction class at Oxford. We briefly touched on organic form structures - that is, departures from the typical Bell Curve, beginning-middle-end, exposition-climax-denouement structure that is often emphasized in western literature. In the piece below I was experimenting with circular patterns and waves. It’s a story I have written linearly in the past, and I was excited to experiment with a different way to explore three interconnected moments in time. Enjoy!

They’re the words you don’t want to hear in this particular medical office: “The doctor wants us to get more pictures.” Naked and sweating from the waist up in my pink hospital gown, I’m terrified that this is it - this is the shoe I'm always waiting to drop.

My feet drop into the pedal cages heavily. I'm fighting my way up the Gil Hodges Bridge. Why is it that the path to Jacob Riis Beach, one of the more beautiful, natural spaces in New York City, has to be separated from the mainland by such a brutal incline, all gleaming metal and man-made structures? I'm not sure I can take much more of this.

I'm not sure I can take another moment in my apartment. It's gorgeous outside, I have no plans and I'm aching for a long ride. But no matter how badly I want to head out, there's always the inertia to be fought before I can get gears turning: the wrestling with padded shorts, the gloves, the helmet, the backpack full of snacks and water, the sunscreen, and, possibly the thing I resist most, stuffing my tits into a sports bra.

The technician stuffs my tits under the plate glass, still warm from the last set of pictures we took. I’ve had enough of these to know the squish-bit isn’t the bad part. It’s the waiting afterward as they review the footage. The very first one I had was the only innocuous one: I was 17, getting a baseline photo before reduction surgery - a reference for future abnormalities. It’s funny, I’ve had loads of abnormalities, and no one’s ever asked for the original view.

The view as I finally crest the bridge is stunning. I relax as I feel my quads get a break, just long enough to see the glittering ocean on the other side of Fort Tilden, before my wheel clips the side rail and everything spins out.

I’m spinning out as I get back to the tiny changing cubicle. The doctor is looking at the new angles and I’m waiting to be told my fate. My heart is racing, my brain is chattering, my stomach is turning. With a family history and naturally lumpy tissue, somehow this moment feels inevitable - I’ve been waiting for my breasts to kill me.

This ride is going to kill me but the ocean is calling. There aren’t many perfect days in New York City to bang out 25 miles of round trip riding. It requires Goldilocks weather: not too hot, not too cold, pleasant but not too sunny - lovely dappled sunlight leads to unseen potholes. And you need plenty of energy, and time. This city will strip you of energy and time.

The timing of the events is impossible to gauge. It all happens so fast I have no idea how I got from my seat to the ground.

I try to ground myself with the years of meditation techniques I’ve learned as a yoga teacher and a Buddhist - try to quiet the catastrophic thoughts, all too rapid.

The rapid turning of the wheel sends a handlebar straight into my chest - hard.

It’s hard to choose exact destinations: Far Rockaway? Breezy Point? Jacob Riis? Wherever it is, water is the point.

The point of the pedal cage gouges my shin, my rim bends, my chain pops off, I fly sideways, landing on my hands.

My hands are sweating as the nurse walks me down the hall to the doctor’s office. Pictures of my breasts are on the screen in front of her when I arrive. What looks like popcorn fills the side of the one labeled “Left.” The doctor’s face is inscrutable. The x-ray is unsettling in its ghostly, black and white contrast.

The contrast between how scared I am and how stunning the view is from the bridge feels like an insult. I’m shaking with adrenaline, trying to get my wheel back to a shape that will revolve, my chain in its place, my leg to stop bleeding. I am alone in a sparsely populated section of a city known for its density.

“The density of your breast tissue always makes it hard to read,” the doctor says, “But I have good news.”

The good news is I get the chain back on. The bad news is I’m miles from the closest subway. I get my breath to slow down, let myself cry a bit, and start a slow limp back to the train, away from the bridge’s trauma.

“Blunt trauma to the tissue. Probably years old. Have you ever had a severe injury to the chest?”

My chest aches where the handlebar struck me, but I don’t realize how badly I’ve been hit; it takes a day for the bruising to start.

I start out the ride in the busy streets of my neighborhood. I brace myself for the upcoming hills. I look forward to the ocean.