Owl Pellets

If you went to Middle School in my hometown vaguely around the time I did, and I said to you now, “Oh my! Soooob Soooob Sob…” or “Jay! Jay! Jay!” in a certain voice, you would know what exactly, and who exactly I was referencing. In 7th grade we all took Life Science, and we all learned bird calls from the same tape (that thing from the olden days with the two holes in it you could rewind with a pencil), and from the same woman’s voice. That woman, who we’ll call Ms. H, was one of only 2 teachers in my scholastic history to give me a C, and a few days ago, at almost-43, the heartbreak of what lead to that grade came flooding back to me.

To caveat, in retrospect a C is a perfectly acceptable grade. Grading is a made up pretend system - just like the taxonomy of birds - and my absolute melt down and genuine terror to receive a perfectly-acceptable-but-not-an-A-or-B grade at 12 years old is a whole other issue, about which I’m not ready to write. But the truth of my experience was that my adolescent self received that grade as a traumatic Saber Tooth Tiger: a memory which has been etched into my amygdala and replayed at odd unpredictable times. However, though I remember the events vividly, what happened to arrive at that grade had been buried in a murky past, and the ramifications of it hadn’t really hit me until now.

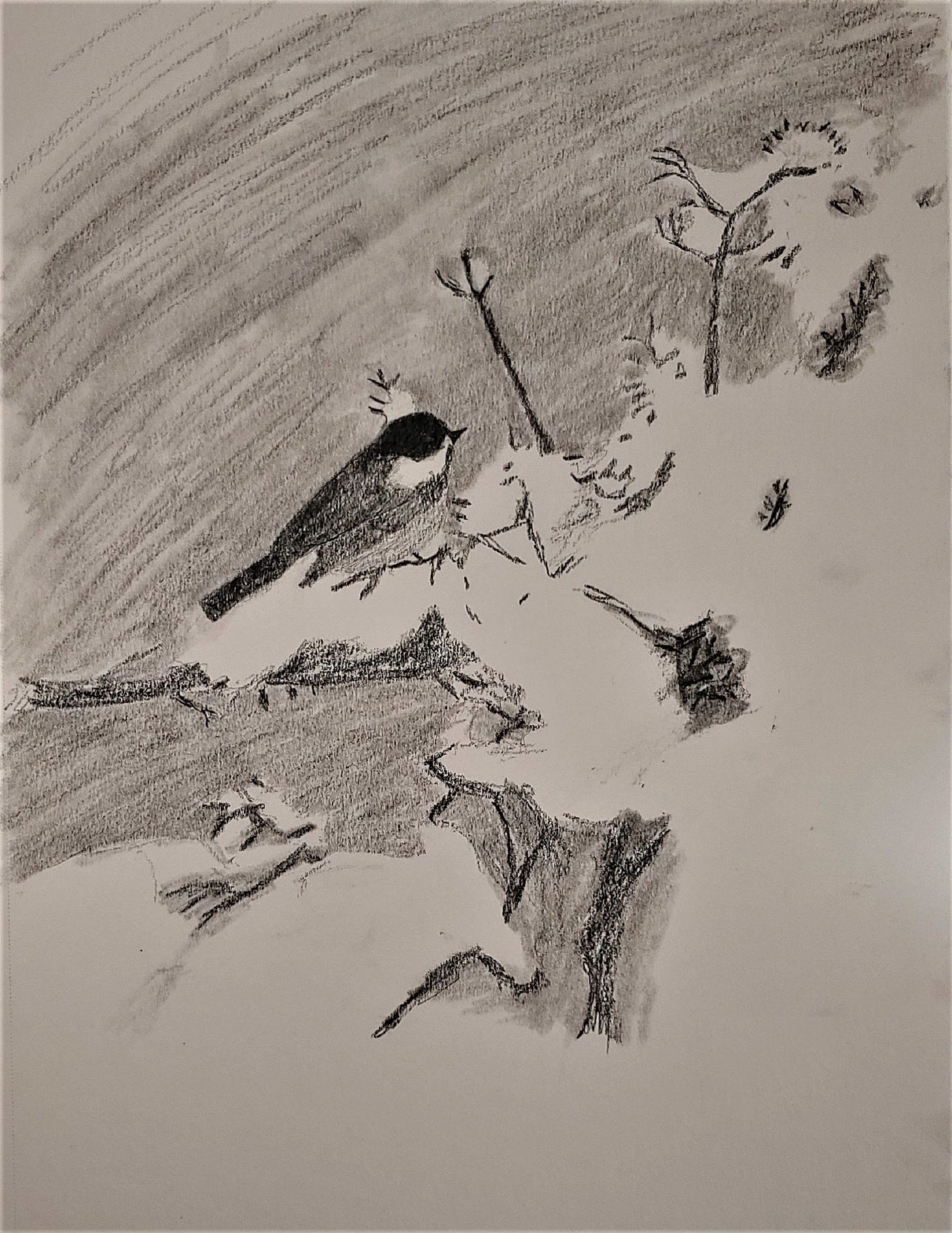

I’m currently reading Amy Tan’s latest release, Backyard Bird Chronicles, a book very like one I was going to write, and now probably won’t because Amy did. It’s a magnificent collection of nature journals, observations and drawings, touching on her return to a love of nature and natural science in later life. To me, it is ultimately about the profound power of quiet noticing. I highly recommend it to anyone, but especially if you love birds, Amy Tan, and/or drawing.

In the Preface, Amy mentions exploring with her young friend-in-nature-observation, Fiona. She writes,

“…in a few days we are going hunting for pellets - the indigestible parts of prey regurgitated by our resident Great Horned Owl. We’ll dissect the pellets to examine the bones, teeth, vertebrae, and fur that are clues to what the owl feasted on.”

It is when I read these sentences a couple days ago - about a relaxed, curious, joyful activity she would engage in on her own time - that I was suddenly overcome with memory and emotion, and hit with 30+ years of loss.

In Ms. H’s class, we had a multi-day (maybe even multi-week) section on owl pellet dissection. Each day we had Life Science, we would work with tweezers and toothpicks to sort tiny bones from the fibrous little nuggets local owls had vomited (stay with me), and glue them to index cards. The graded final project was to have a full skeleton of a creature with all bones labeled.

But this particular activity was not the blocked memory that came flooding back - I have thought about this project often. I could not finish my skeleton in time, could not find every bit of bone or correctly identify every tiny vertebrae. I basically failed that project, and though I excelled at the prior bird-call identification unit (I’ve known my Black Capped Chickadees and Tufted Titmice for a LONG time) and did ok on the leaf identification (though not great), she informed me at an excruciating conference with my mother that if I hadn’t done the couple of extra credit projects earlier in the year, I would have potentially failed the class entirely.

Because of the damn pellets.

It is hard to remember being a child obsessed with achievement told they had teetered on the edge of failure. But that isn’t what hit me the other day. The lost pain that came flooding back to me on a warm day in May 2024, 30+ years later, was what I had completely forgotten about doing the project…

I loved it.

The trauma of the perceived failure has totally eclipsed for all these decades that I actually loved doing it, and that love, through our scholastic obsession with a (Capitalist?) relationship to speed and time, stole that love from me for years.

I loved it. I loved the dissection, I loved the exploration, the discovery, the creative, artistic element of reforming the skeleton. I loved the understanding of the cycle of life. I loved all of it as much as I had loved learning bird calls and even my mediocre understanding of leaf shapes. But when I finished 7th grade all I can remember thinking are the now soul crushing words…I hate Life Science.

It took me years and a pandemic to come back to that sweet little kid that just wanted to be in nature, observe phenomena, and have as much time as she needed to do so. As an educator now myself, and as the mentor to an almost-17-year-old who is stressed to the point of physiological detriment from school, I am struck by the damning power our scholastic relationship to time can be.

My heart goes out to Ms. H in some ways. She was just working within a system that required grades and completion points and rubric. But I am also very, very angry, and processing incredible grief for time lost from connecting to a vibrant part of my inner life, through outer exploration of the natural world. How different would my path look if that slow, meticulous little girl were just given more time? If the flame of interest had been fanned, and not smothered?

I am deeply grateful to Amy Tan for bringing up this hard memory. Grief, I belief, is always valuable to process, especially if it is old and cloudy. I think it is not a coincidence that this processing moment has arrived at a time in my life when I am writing my own syllabi, designing my own classes, and considering my values as an educator. The influence we have as teachers is so precariously powerful. I know I will fan some flames and potentially smother others, and have to be forgiving and gentle with myself as I continue this journey.

But if nothing else, may I vow to never quash a love of curiosity and exploration of any kind, because of my own relationship to time. May my students always dissect their pellets, whatever they may be, for as long as they need.